Selection and self-selection of junior researchers

This news appears in the BUA newsletter in August 2024.

Is science in a position to recruit the staff it needs or is it at risk of falling behind the non-university labour markets due to the in some respects difficult working conditions and career prospects? This question was analysed from two angles in the latest wave of the Berlin Science Survey. Firstly, on the basis of the career goals of pre- and postdoctoral researchers and secondly, on the basis of assessments of the recruiting situation in various subject groups.

In discussions about the situation of junior researchers, precarious employment conditions and a lack of career prospects are often addressed. At the same time, a lot is currently happening on the labour market: Generation Z is questioning previous standards and companies are reacting to the changing demands of their employees. In this context, the question arises of how attractive science is as a workplace. To what extent is academia able to recruit the personnel it needs or is it in danger of falling behind the non-university labour markets?

In the latest wave of the Berlin Science Survey, these questions were analysed from two angles: selection and self-selection. On the one hand, questions were asked about the recruiting situation, i.e. the possibility of finding suitable candidates. On the other hand, the career goals of young researchers were questioned, which reflects self-selection. Who would like to stay in academia and sees here a professional future for themselves?

The dominant logic in science policy and management to date assumes that there are enough suitable and highly motivated scientists striving for a career in science and thus there is a large pool from which suitable or even ‘the best’ candidates could be selected. This assumption often goes hand in hand with another one, namely that these candidates want a career in science so much that they are willing to accept some hurdles and difficulties on these way. But the wind seems to be changing. Not only have the rather poor working conditions and prospects been known for some time, especially in mid-level positions, but the attractiveness of a professorship as a job profile is not (or no longer) consistently rated positively.

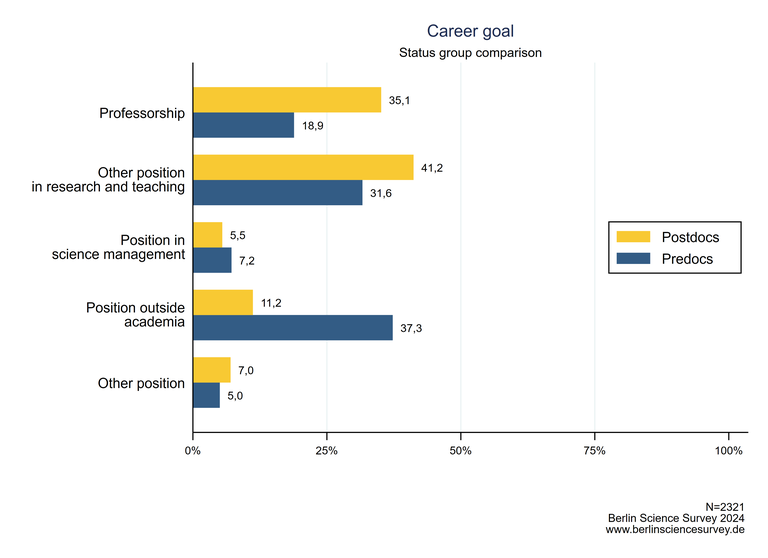

Against this background, the findings from the BSS regarding career goals are not surprising (Figure 1). Although the majority of the scientists surveyed would like to remain in academia, the majority of them are aiming for a position in research and teaching other than a professorship. 18.9% of predocs and 35.1% of postdocs indicate a professorship as their career goal. The proportion of postdocs who aspire to another position in research and teaching is significantly higher at 41.2%. A further 5.5% of postdocs aspire to a position in science management. The high proportion of doctoral students with a career goal outside of science (37.3 %) reflects the fact that the German higher education system traditionally trains many doctoral graduates for the external labour markets and not just as its own next generation. The extent to which these distributions reflect individual preferences or assessments of opportunities cannot be determined from the data.

For early career researchers, it is important that they are well prepared for career paths within and outside academia. Only then can they ultimately decide freely which career path they want to take. And only this brings the institutions in a situation to have a chance of recruiting the most suitable and motivated candidates.

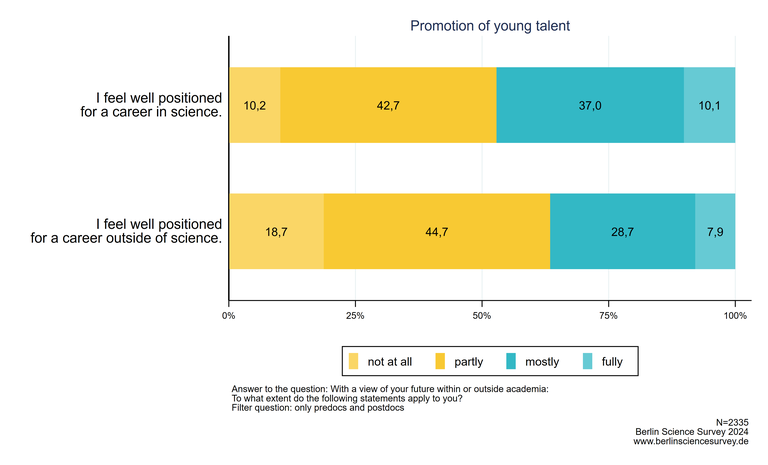

Fig. 2 shows how well or bad mid-level academics feel prepared for careers within and outside academia. Only around half of mid-level academic staff feel well prepared for a career in academia (see Figure 2). At 36.6%, they feel even less well prepared for careers outside academia.

21% feel well positioned for both paths (not shown). At the same time, 38% feel that they are not well positioned for a career path within or outside academia. So there is still a lot to be done in the area of promoting young talent!

What does the situation look like on the selection side? Can the institutions (still) access enough suitable applicants or have too many already decided against a career in science?

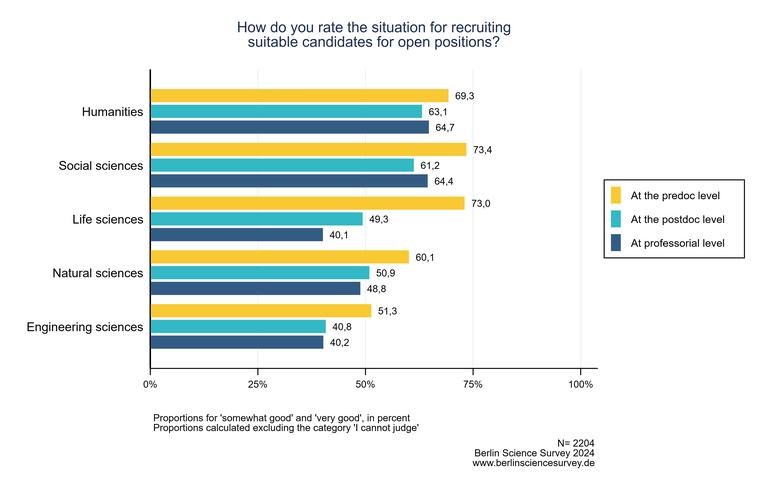

The result is mixed (Figure 3). Not in all areas is the recruiting situation sufficiently good. Differences can be seen depending on the career level and, not surprisingly, with regard to different subject groups. In the humanities and social sciences, but also in the life sciences, the recruitment of suitable predocs is largely unproblematic. Here, around 70% of respondents rate the ability to attract ‘suitable candidates’ as rather good or very good. In the natural sciences (60%) and even more so in the engineering sciences (51%), filling predoctoral positions already cause difficulties in some cases. The situation is somewhat more difficult for postdocs in all subject groups: here, only between 63% (humanities) and 41% (engineering) state that the recruiting situation is (rather) good. The recruiting situation for professorships differs from that for postdocs only in the life sciences. A clear drop can be observed here, i.e. only 40% still rate the recruiting situation as good. In the humanities (65 %), social sciences (64 %), natural sciences (49 %) and engineering sciences (40 %), the recruiting situation does not differ from that at the postdoctoral level.

In the STEM subjects, the majority of respondents rate the recruiting situation for postdoc positions and professorships as somewhat bad (see Figure 3). This shows that the subjects with good career opportunities outside academia are already struggling with inadequate recruiting situations in some cases. It can be assumed that under the current labour market conditions, the increased demands of Generation Z and improved working conditions outside academia, the difficulty of attracting suitable candidates will increase across all disciplines. It therefore seems essential that scientific institutions and science policy also rethink their previous ‘logics’ and make adjustments here. It is important to make science as a profession more attractive overall and not just count on the intrinsic motivation of scientists. In addition to the much-discussed employment conditions and career paths for mid-level staff, this also includes the attractiveness of professorships and their working conditions.

The Berlin Science Survey

The Berlin Science Survey (BSS) is a scientific trend study on cultural change in the Berlin research landscape. To this end, the Robert K. Merton Centre for Science Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin regularly surveys the experiences and assessments of scientists in the Berlin research area online. A total of 2,767 scientists from the Berlin Research Area took part in the latest study, which focussed on the topic of ‘’General conditions for good science‘’. We would like to thank everyone who took part in the study. The various and sometimes complex topics of the current survey will be successively analysed over the coming months and the results published.